How to be civilised

Written by Richard Docwra

The Holocaust is a relatively recent event, but is such a horrific period in human history that many of us just don’t want to contemplate it. Yet, if we summon the courage to really reflect on what happened, we can draw out some profound and important lessons - both for our own lives and for society at large.

This booklet - aimed at adult readers - considers 8 lessons from the Holocaust that could help us live better lives. For example, the fact that civilisation is a fragile thing and we need to put more effort into protecting it in our everyday lives.

How to be civilised

Introduction

The Holocaust is a period in human history that has been written about at length, and permanently burned into the collective consciousness.

But how much have ordinary individuals in the modern world really learned from it? How much have we - beyond scholars - really delved into this dark period and extracted all the lessons we need to learn? According to the Holocaust Education Trust (HET), “In England, by law children are to be taught about the Holocaust as part of the Key Stage 3 History curriculum. This usually occurs in Year 9 (age 13-14)”. It is also taught across other subject areas including History, Religious Studies and Citizenship.

So, children are given some education on this issue, but this teaching tends to treat the Holocaust more as an issue for our society and politics as a whole, rather than providing a rich and important set of lessons for how we should think and live our own lives as individuals. It also fails (with the highly laudable exception of organisations like the Holocaust Education Trust) to get people to explore the topic in enough depth to bring out the necessary lessons and insights we need to learn.

This is not simply an issue to educate children about, though. We also suggest that most adults have not truly taken the lessons of the Holocaust to heart - and here are a few possible reasons why:

- Some may think it can be consigned to history - a ‘blip’ in the human story - and that it’s not relevant to them any more. As we will see though, this is clearly not the case.

- It is a difficult, unpleasant topic to think about and discuss - and is easier to ignore.

- There is little education or awareness-raising on this topic for adults.

- In our education system it is recognised more as a historical event rather than as a ‘live’ issue that affects us now.

- When we do consider the Holocaust, the topic is often ‘sweetened’ by focussing on stories of hope within the tragedy. With notable exceptions (like Anne Frank) the stories we often hear from this period seem to be mainly those of survivors, whose tales offer a certain level of hope and redemption due to the person’s survival. But there are obviously millions of people who didn’t survive - and it’s important to understand what they went through, as we are trying to get to grips with the reality of what happened (no matter how difficult it may be to think about) so that we can genuinely learn something, rather than simply grasping for hope because it makes us feel better.

So, we are not doing enough to learn from the Holocaust. But why does this matter?

First, and most obviously, the Holocaust is such a traumatic and extreme set of events that it should always be something we come back to review. Indeed, the very minimum we should aim to gain from it is an insight into how human beings and societies work, and the thinking and behaviours that we can fall into under certain circumstances, so that we can do everything in our power to ensure that it never happens again. It would be an appalling betrayal of the millions of victims if we failed to do this.

The fact that genocide has taken place since the Holocaust (and continues to take place) shows either that we have failed to learn the lessons of the period or that our propensity for this sort of extreme behaviour is greater than we like to think. In truth, it is probably a mixture of all these things, so this again confirms the idea that you can never examine the lessons of the Holocaust too much. Perhaps it is too much to hope to eliminate the possibility of genocide and extreme human cruelty, but anything we can learn and do to minimise it must surely be a good thing.

Another key reason why everyone should be encouraged to examine the Holocaust in more depth is that it (and other periods like it) holds some profoundly important lessons and insights for us as to how we should live our daily lives – and raises many complex questions about morality, what human beings are and many other issues – including what we should teach our children.

So, in conclusion, we need to encourage everyone - adults and children alike - to face the reality and lessons of the Holocaust. We therefore need to not only improve the way we educate children on this topic, but adults too. We also need to ensure it is seen as a ‘live’ issue – one that could affect our lives just as much today as it did people in the 30’s and 40’s, and ensure that, amongst our teaching on the Holocaust we use it to teach people insights and ideas to use as life skills in their individual lives - including the simple but vital concept of ‘civility’, which we will discuss in this article.

But why are we just focusing on the Holocaust here? Clearly there are many other horrific historical events we could use to derive lessons from. We’ve chosen to focus on this one partly to keep things simple (there is more sustained complexity in the Holocaust alone than we can possibly even scrape the surface of here) but also because, despite its status as one of the key events in the course of written human history, it is shocking how little we’ve used it to make the world better or teach each other life skills.

In this booklet - aimed at adult readers - we will therefore explore what we think is one of the most neglected aspects of learning from the Holocaust – the lessons it provides for our own lives as individuals. Ultimately, it’s a plea for us all to learn the lessons that our tragedies teach us. Naturally, in a short booklet we don’t have enough space to discuss these issues in the detail they deserve but we’ve kept it brief enough to make it accessible for readers and to raise some of the issues so you can explore them in more detail afterwards if you would like to. For this reason, we’ve added some suggested resources for further reading and information at the end of the booklet.

Part 1 - The reality of the Holocaust

Facing what happened

Before we discuss any of the lessons or insights to be gained from the Holocaust, we should make sure that we are seeing it clearly and with sufficient impact.

There’s an obscene draw towards looking at the Holocaust in terms of statistics - 6 million Jews, plus millions of other people, killed - one almost marvels at the horror of it. But packaging it up in terms of shocking statistics and putting it into the past feels like a way for us to distance ourselves from it and gain some control over it, which almost makes it too easy to deal with. As Stalin (who knew about these things) is reputed to have said: “A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.”

Certainly there are lessons to be learned from seeing the Holocaust in this broad way, but one could argue that there are more lessons to be learnt when we try to face up to the human horror of it by putting ourselves in the shoes of the victims as real people, understanding the situation they faced and seeing how the situation developed over time. Remember, these were ordinary people who went from living lives like yours or mine to being treated as non-humans and exterminated as vermin.

It requires a strong constitution to throw oneself into the horror of this situation, and many people simply don’t want to think about it at this level of depth – summoning the courage to truly put ourselves in these people’s’ shoes and think about their situation. But it feels like the least we can do in tribute to these individuals – partly because it could be us or people like us in their position in the future, but also because the lessons we learn may help us to both live our lives better now and do our bit as individuals to prevent such a situation from occurring in the future.

But even when we try to look at the Holocaust from a human perspective, we can sometimes fail to connect with it deeply enough. We normally see the Holocaust through black and white photographs of Jewish people walking through towns wearing star of David armbands, inmates of concentration camps staring at us with blank expressions or piles of dead bodies lying in similar camps. These are horrific pictures and may well be the maximum most people can bear to tolerate - but they still perhaps prevent us from empathising and seeing this situation fully and clearly enough. We don’t need to see snapshots – we need to hear stories, experiences – and put ourselves in people’s shoes.

In theory, film can help us to do this. In the modern world of instant global communication we are used to seeing visceral pictures of news events, including people’s suffering. But the events of the Holocaust occurred in an era before that of mobile phone videos and global reporting, which limit the amount of personal video available. Also, much of the suffering took place within the barriers of a despotic regime, which made it difficult for people to record or transmit information - just consider, even today, how difficult it is to gain real information from countries like North Korea. As the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum notes, “The audiovisual memory of the Nazi era remains heavily influenced today by the official images created by the Nazi propaganda machine.”

All in all this makes it difficult to get lots of video footage to tell the stories at the level of intimacy we need. Instead of films then, what we may need to do is create our own films in our own heads of what it was like.

Let us therefore have the courage to step into this and face it.

Imagine how bereft, sickened and emotional you feel when you look at a video of children starving in a famine, with their parents unable to do anything to reduce their suffering. Then imagine this situation again, but in a rich western country, and being deliberately and systematically imposed on a specific group of people by a government and its soldiers and institutions. Imagine also, while this suffering is being publically endured by millions of individuals, other citizens of their countries and towns – indeed, former friends and neighbours - are living alongside them in broad daylight and deliberately doing nothing to help - and in fact, are actively participating in these people’s misery. Then imagine these tragic people being summoned into groups in their own town squares, herded onto trains to go to destinations they know very little about, and on arrival being separated from their loved ones and children and taken to horrific and confusing deaths. Once you have imagined this, you will then be getting a little closer to the reality of the Holocaust.

This did not happen in another world to ours - history is simply the story of ordinary people like you and I living at a different point in time - it happened in towns and villages like ours, to people like us.

Let us explore one or two stories from specific people, to give a real view. Take this transcript of an interview with Charlene Schiff (taken from the United States Holocaust Museum archive), describing conditions in the Horochow ghetto in Poland in 1941, when she was 12 years old:

When we were thrown into that ghetto, we were assigned one room. It was a large building, actually as far as I recall it was a three-story building. It was in the poorest section of town, and it was very, in great disrepair. We were assigned this one room, and there were three other families with us to share that one room. The entire house had one bathroom and one kitchen, and the running water was almost nothing, I mean there was very little water. There was no warm water, only cold water. If you wanted hot water you had to heat it on a wooden stove, and there was no wood. Uh, the, the, there was not enough room to sleep everyone on the floor in our room, and so the women - and there were two boys in that group - found some wood and they built, uh, bunks, I guess, so that we slept like in threes, because there was not enough room for all of us. Most of the people in our room were people who went to work. There were only, I think, three, four of us who were, uh, not quite 14 years of age, and we are the ones who were left at home in the house to fend for ourselves in the very beginning.

The people who did not go to work did not receive any rations. The rations were very meager. I am not quite sure the, the weights, but it was like maybe two slices of bread, some oleo, a little bit of sugar, and I think some vegetables. I don’t think there was any meat at all, and these rations, first they were given daily, then when the Judenrat organized everything it was done once a week, and usually by the second or third day everything was gone. My mother and sister shared their rations with me. It was very difficult, and in the beginning there was an awful lot of chaos. Uh, the kids, like myself, the younger, were really left with nothing to do. We were very hungry. We were dirty. We were unsupervised, and it was very difficult to comprehend what really went on. We ate only at night, when our parents or whoever took care of us came home, and all day there was nothing to do.

Consequently, the kids, like myself, decided that we had to go outside and try and get some food. It was an unbelievable feeling to be hungry and it, it’s, it’s a hunger that is very difficult to describe, for a child to be hungry, and there was nothing to eat. And, when I was asked, uh, many times what did we play, what did we do, we pretended, and what we played about mostly is about food. We talked about food, we pretended about – I mean, everything centered around food.

To see a video of Charlene’s full interview and other people’s stories, visit www.ushmm.org/exhibition/personal-history/.

Here is an extract from another story, courtesy of the Holocaust Educational Trust (www.het.org.uk).

Freda Wineman was born on 6th September 1923, in Metz in Lorraine, France. When she was eight she moved with her parents, elder brother, David and younger brothers, Armand and Marcel, to Sarreguemines, which was near the French border with Germany.

In August 1939, as war was looming, the whole town was evacuated to south-west France. Following the German invasion of 1940, life in France became increasingly difficult for Jews, and Freda’s mother approached a convent to see if they would hide the family. Although the convent agreed to help, the family were arrested before they could go into hiding and were sent to Drancy transit camp on the outskirts of Paris.

From Drancy, the whole family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. As soon as they arrived they had to undergo a selection, where SS officers decided who was fit to work and who was to be exterminated. There were a number of prisoners surrounding the new arrivals, and they told the older women to take babies from the younger women. Freda’s mother took a baby from a young Dutch woman and was sent to one side with Freda’s brother, Marcel. Freda followed her mother but was told to stand in the other line, as her mother would be looking after the children. In fact they were being sent to the gas chamber. Freda was taken with the other women selected for work. She was disinfected and tattooed with the number A.7181.

Soon after arriving, Freda was selected to be part of a work detail known as the Kanada Kommando. They worked very close to the gas chambers, sorting the belongings of prisoners and those who had been murdered. Whilst she was working here, three of the girls who worked with her were caught smuggling clothes back into the camp and hanged. Freda and the other women from this group were then taken away from the Kanada Kommando and worked digging trenches in front of the crematoria until the Sonderkommando revolt of October 1944. On 30th October 1944, soon after the Sonderkommando revolt, Freda was taken from Auschwitz by cattle trucks to Bergen-Belsen, where she remained until February 1945. From there she was sent with 750 other women to Raguhn, a satellite camp of Buchenwald concentration camp, where she worked in an aeroplane factory.

As the Allies advanced, Freda was once again put on a cattle truck and sent to Terezín (Theresienstadt), where she arrived on 20th April 1945 and remained until she was liberated by Soviet troops on 9th May 1945. After liberation,Freda discovered that her parents and her brother, Marcel, had been killed at Auschwitz. Her brothers David and Armand had both survived and she was sent back to Lyon on 4th June 1945 to be reunited with them. In 1950, Freda married and moved to the UK, having two children. Her husband David later died aged 42. In January 2009 Freda returned to Auschwitz and her visit was featured on Blue Peter as part of their Holocaust Memorial Day commemorations. Freda continues to live in London and share her testimony with students across the UK.

These are just two of the many, many stories that have been gathered and stored since the Holocaust took place. They all invite us to think about the sheer scale of what happened and what would happen if our lives were affected in the same way - as these were people like us, going about their ordinary lives. We often think ‘it could never happen to us’ but this is exactly what many of these people thought. It was a level of mass-scale brutality that people just didn’t think was possible – but it is - and this disbelief was one of the (many) things that actually enabled it to happen as it did. Also, the fact that it has happened once doesn’t mean that it won’t happen again - as has been proved by other events of a similar nature since.

Part 2 - 8 lessons to learn

There are clearly countless lessons that we can learn from a human tragedy of the scale of the Holocaust, but in the space of this booklet we have had to focus on a limited, specific range of points, so below we will outline 8 points that we think have particular relevance for our lives now - in the modern world, at a time of relative (but not entirely stable) peace.

1. The sheen of civilisation is thin

We take civilisation for granted. We rarely question the idea that we can walk around freely living our own lives, without much danger of being attacked or oppressed by others. We assume that other people will be pleasant to us and we will generally cooperate and live harmoniously with each other, and are shocked when there is a ‘wobble’ in this harmony – even when someone says something rude to us.The idea that this normal state of affairs could be completely shattered is unthinkable to us - we simply don’t entertain this thought in our daily lives.

The first lesson we should learn from the Holocaust and events like it is that this smooth, co-operative surface of civilisation that we all skate upon is very thin, and can be shattered with relative ease.

This is backed up by people’s reactions to relatively minor events. For example, in 2010 lorry drivers blockaded some oil refineries in protest at rising fuel costs in the UK. This led to a few days of petrol shortages, but even in a minor crisis like this, we saw large queues of cars at many garages, with drivers competing to fill their tanks, engaged in panic buying to stockpile fuel. A couple of days into the crisis, this panic buying extended to the supermarkets, with people stockpiling supplies of tinned goods and other items. As the time this felt like an extraordinary reaction to a relatively modest crisis, and it shows how quickly we can revert back to the ‘state of nature’ described by Thomas Hobbes in his classic book ‘Leviathan’.

To give another example, a wave of looting, rape and armed terror hit New Orleans within hours of Hurricane Katrina striking the city in 2005. The chaos of a natural disaster seemed to give rise to a human

disaster. Despite all the other aspects of this tragedy, such as “the incompetence of the Bush administration, the scandalous neglect of poor black people in America, or our unpreparedness for major natural disaster”1, historian Timothy Garton Ash suggested that the big lesson to learn from this event was the city’s quick descent into this state of what he termed ‘de-civilisation’.

The conclusion of this first lesson is as follows - it’s a fine line that separates civilised society from de-civilized, and we shouldn’t take our state of civilisation for granted, but cherish it and work tirelessly to protect it.

2. Our day-to-day actions are the thin end of the wedge

The perpetrators of the Holocaust performed appalling, evil acts. But they couldn’t have done so without the tacit acceptance and cooperation of millions of other people in Germany and other countries, who were willing to turn a blind eye to what was happening. Some would claim ignorance of what was going on, but this is no excuse, as even if some weren’t aware of the full horror of what was taking place (and many were aware of rumours to this effect), it was impossible to avoid the fact that Jews and other group of people were being treated in an inhumane way.

The reality is that many people turned a blind eye to what was happening because they actually shared the views and prejudices of the Nazis - perhaps not to the same extreme degree as the architects of the Final Solution, but nevertheless sharing enough of the basic prejudices that allowed them to ignore, condone or even support what was happening.

This leads us to another conclusion from the Holocaust - our minor prejudices and little cruelties are the thin end of the wedge for much bigger horrors. For example, lashing out at people when we’re tired, letting our tempers flare in a road rage incident or the negative thoughts and lazy prejudices that we keep in our heads most of the time that judge, and separate us from, other people. This is not necessarily because these thoughts or behaviours have substantial impacts themselves individually (our muttering under our breath that ‘we should get rid of those immigrants’ isn’t likely to directly affect anyone), but because they foster an attitude in our own minds that this thinking and behaviour is acceptable, and the more we let ourselves get away with it, the more likely we are to let ourselves accept bigger things in the future, so that less and less ‘civilised’ views and behaviour seem less radical as our standards drop.

This not only the case for how we think and behave as individuals, but also affects other people, as when we share these views and act out this behaviour it sets an example to others (not just children but adults too) - and gives a sense that these sentiments and actions are acceptable in society. They also create a less civilised, compassionate atmosphere - just consider the difference in atmosphere between a football terrace and a meditation retreat centre.

It’s also worth reminding ourselves that terrible events such as the Holocaust did not take place in a completely different world to our own, occupied by completely different creatures - they took place in houses like ours and in streets like ours, populated by people like us. There’s a certain mundanity to violence and terror - they can become everyday actions if we let them become so.

Sometimes we fail to see this though, as when we watch a film or see the news, terrible and violent events often seem to take place in a spectacular way - from big explosions to massive gun battles. But violence and terror aren’t necessarily spectacular or even physical things - they can consist of a harsh word, a slap around the face or a sustained period of bullying. For example, the charity Women’s Aid defines domestic abuse as “an incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening, degrading and violent behaviour” - a range of behaviour types besides direct violence, each of which can lead to terror for the victim.

Even a murder can be unspectacular. There are plenty of examples of hitherto ordinary people committing violent crimes after everyday things simply got ‘out of hand’ - events escalated, they failed to control their emotions or behaviour and and they ended up committing an act or acts that they would not have imagined themselves doing. People sometimes fail to see which of their thoughts or actions could sow the seed for violence or terror, or recognise when when their thoughts or actions have crossed the line into this state of affairs (e.g. into coercive behaviour) - and perhaps we need to make people more aware of this.

When we see it like this, we should not be so surprised that something like the Holocaust can take place in a seemingly civilised country. It starts with each of us - when we harbour lazy, prejudiced views, behave badly towards each other or careless in how we set our own standards of thinking and behaviour, we allow ourselves to get ever closer to these depths in everyday life.

The point is this - it takes discipline and effort to behave in a civilised way - to have the patience and awareness not to pre-judge someone, to have the courage to apologise for a cruel statement or have the self-discipline not to behave aggressively, even when it would be easier (and perhaps temporarily more satisfying) to not do these things. But by putting in this effort we draw a clear boundary for ourselves - and other people - of what kind, civilised behaviour looks like.

3. Empathy is humanity

Our capacity to empathise with the feelings and situation of others - and to see them as human beings rather than ‘other’ in some way - is absolutely fundamental to our ability (and willingness) to treat each other well and, ultimately, to be civilised. We are capable of acts of extreme cruelty when we fail to see other people as human beings.

The Nazis recognised this point, and the process they went through to ‘de-humanise’ their victims in the minds of other people (from making them look filthy and smelly to seeing them as ‘vermin’) was vital in their ability to get the public to accept the cruelties and injustices being inflicted in their name, as well as to reassure soldiers and other participants in the killings and other horrific acts that they should actually carry them out.

We therefore need to promote the idea of empathy as a life skill for people, cherish and protect it and make people aware of its importance, as well as what the world could be like (and has been like) in its absence. Going back to the previous point - the ‘thin end of the wedge’ lesson - we should all exercise the discipline and self-awareness to check and correct ourselves whenever we find ourselves thinking of people (whether groups or individuals) as ‘other’ or somehow not as human as the rest of us.

A final point regarding empathy is that we need to be constantly aware of how our actions affect other people - and empathy is an important skill enabling us to do this. It helps us to exercise the golden rule - an important heuristic for living a civilised life if ever there was one - as espoused by thinkers from Confucius to Jesus to Kant - ‘treat others in the way you wish to be treated’.

4. It’s not just evil people who do bad things

One of the reasons that Hannah Arendt’s book ‘The Trial of Adolf Eichmann’ created so much controversy on its publication in 1963 (and has done ever since) is that it portrays one of the key men in charge of the extermination of the Jews not as an evil monster driven to oversee unprecedented mass murder by hatred for the Jews but as someone who ended up committing and enabling unspeakable acts due to a mixture of personal ambition, bureaucratic diligence and general thoughtlessness. To quote Arendt herself:

“Except for an extraordinary diligence in looking out for his personal advancement, he had no motives at all.” 2

This insight outraged the people who wanted Eichmann and all the other perpetrators to be portrayed as amoral monsters, but actually provides us with a profound, if troubling, lesson about human beings. There may be some people in the world - a small minority - who could be described as deliberately evil. These people perhaps have no concern about destroying other people or the fabric binding society together. Alongside this tiny minority however are the rest of us. We are neither good nor bad (as no such classification really exists beyond human cultures that made it up and use it - we either think and behave in ways that are seen as admirable to society or not).

A surprising observation made by many commentators on the Holocaust was how the Jewish victims largely went quietly and co-operatively to their deaths. There were of course stories of resistance, but these were the exception rather than the rule. There are many possible reasons for this compliance, and one could have been that the victims simply failed to believe it was possible for people to do such appalling things to each other on such a massive scale. But a more realistic and nuanced understanding of human beings would show us that we do have the potential to carry out these acts.

So, a lesson from the Holocaust (and the everaccelerating advances in neuroscience and psychology in recent years) is that most of us are capable of acts of extreme evil under certain circumstances. There are a range of ways in which we can struggle to behave morally. For example, when we are influenced by other people. Human beings are social creatures, and we not only like to be accepted by other people but we are also influenced by the values and cultures in which we live. The Holocaust presents a good, and shocking, example of how a culture’s values can shift and people’s own moral compases and instincts can be dulled, influenced and shifted as a result. As Amos Elon notes in his introduction to ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’ by Hannah Arendt:

“In the Third Reich evil lost its distinctive characteristic by which most people had until then recognised it. The Nazis redefined it as a civil norm.”

So, this is just one of the ways that previously ‘normal’ people might end up doing evil things. We therefore make a mistake when we expect people to be purely moral creatures - as our desire to behave

in ways we would describe as ‘pro-civilised’ is just one of the factors driving us. Other factors, such as social influence, can be equally powerful drivers of our behaviour.

This does not mean that people are naturally ‘bad’ (or indeed ‘good’) - and we need to get away from this ‘moralised’ way of characterising human beings, as it is outdated, reductive and inaccurate. It leads us to adopt inaccurate expectations of people, including giving us a ‘blind spot’ to miss people’s propensity for de-civilised behaviour (‘people just aren’t capable of that’) and making people’s lives a misery by imposing pressure and guilt on them to conform to impossible and arbitrary ideas of ‘goodness’ (certain religious ideas are just one example of this). So, we are neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’ - we are human - in other words, creatures with a complex biological makeup and ways of reacting to external stimuli.

Another example of this biological makeup that we are generally mistaken about is the traditionally-held idea that human beings are completely ‘rational’ in our thinking and behaviour. In society at large, we’ve held the belief for some time that people are rational actors, basing all our actions on considered thoughts made in our brains. But research in recent decades (perhaps most notably by Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman - see his book ‘Thinking, Fast And Slow’ for details4) shows that this is not the complete picture, and we are in fact more reliant on our intuition and ‘short cuts’ in our thinking than we thought.

Overall the reality is that we are different creatures from those most of us think we are. Scientists and psychologists are only just starting to develop a better appreciation of how humans think and what we are truly like, but even at this relatively early stage, we can see that the model of a human that we have been using and teaching each other for centuries is incorrect - and that we urgently need to start

educating people, adults and children alike as to what a more realistic picture of human beings looks like. If we do this, we may find ourselves better able to consider some of the innate ‘vulnerabilities’ that people (as individuals and populations) might have towards de-civilised behaviour, and if it is necessary, reasonable and desirable to do so, take steps to prevent this behaviour happening - such as educating people about these vulnerabilities.

5. Inaction is an action – and it can lead to evil

Within the Holocaust (and doubtless in other atrocities too) there are countless examples of where people allowed bad things - things they actually disagreed with - to happen without challenging them. These ranged from the rise of dubious political ideas through to terrible things happening in front of them in broad daylight. This lack of reaction might have been for a whole host of reasons, including (a justified) fear of punishment, a desire not to ‘rock the boat’ or simple laziness.

This happened among the populations of Germany and various other European countries, as well as politicians, soldiers and other individuals. At the most extreme level towards the top of the Nazi hierarchy, it could be said that Eichmann himself was guilty of a failure to act - or more specifically, a failure to think. He carried out his duties, but simply failed to challenge himself or think through their context or consequences. And this led to him committing acts of great evil. As Hannah Arendt noted:

“He merely, to put the matter colloquially, never realised what he was doing.” 5

The point here is that we all have the choice on whether to take action and speak up or not - at any point in our lives. Taking no action - and not speaking up – is a choice, and is an action. Being passive is an action. It only takes people to adopt a particular attitude (they don’t need to take any action - merely to accept or condone the actions of others) to enable more energetic people with an agenda to perform unspeakable acts of cruelty and horror in their name. It only really needs one person with an agenda and a compliant public to enable terrible things to happen - things that previously seemed impossible.

Not only can doing nothing lead to you failing to stop evil things happening - it can lead to you actually becoming a perpetrator of evil.

6. Resistance is useful

In fact, it’s sometimes all we’ve got.

Another reason why most of the victims of the Holocaust may have gone quietly and co-operatively to their deaths could be that, linked to their failure to believe that people could do such appalling things to each other, the victims kept a sense of hope until the last. As survivor Viktor Frankl notes in his account of life in a concentration camp, ‘Man’s search for meaning’:

“We, too, clung to shreds of hope and believed to the last moment that it would not be so bad.” 6

And it was perhaps this sense of hope that stopped a proportion of victims from risking their lives in acts of resistance. This natural desire to hope was cynically exploited by the German soldiers running the deportation and extermination process, who provided (empty) reassurance at each stage – from the chief of the Lodz ghetto, Biebow, telling Jews they were going to move them east to save their lives7 through to soldiers at the entrance to the gas chambers telling people that they would receive soup and then work after they’d had their ‘shower’8. The Germans knew that their ability to carry out the Final Solution depended on having compliant victims, and the need for secrecy and reassurance was critical to this.

The fact is though that the Germans were scared of resistance from Jewish populations as they implemented their plans. And on the most notable occasion they were met with resistance – the end of the clearing of the Warsaw ghetto – this did appear to inconvenience them and slow them down. So, although most acts of rebellion were met with terrible force by the Germans (as promised) the occasional resistance that did take place suggests that the Jewish population could have avoided the scale of losses that it suffered had there been more acts of organized rebellion. As one of the killers himself, Anti-Partisan Chief and Higher SS and Police Leader Russia Center von dem Bach, said:

“If they had had some sort of organization, these people could have been saved by the millions.” 9

Our first conclusion from this lesson is therefore that we each need to have more confidence in, and take more responsibility for, our moral instincts as individuals. To follow our own moral judgement rather than being swayed by those of others so that we are less open to manipulation on this.

The other lesson is that we need to challenge and question things that instinctively don’t seem right, fair or just to us, and to speak up when our instinct or conscience tells us to - even if this just in relation to a minor incident in daily life - as this ‘practice’ could give us the strength we need to stand up in the future when it really counts, if we are called on to do so.

An idea, policy or sentiment doesn’t need to be good or logical for it to spread in a society. It can be planted by force, through propaganda and other means. And once it starts to gain traction in a population, its growth can be very hard to stop, as it can be reinforced by many factors entirely unrelated to the veracity of the idea itself, such as people jumping on the bandwagon for reasons of fear or self interest. When it gets to this point, it is only people with the awareness of their convictions, and the courage and sense of broader social duty needed to express and stand by them, who provide hope.

And make no mistake - it does take courage to do this - to go against our instinct for social acceptance (which is not always the same as ‘pro-civilised’ behaviour, by the way) and stand up for ourselves – especially when it feels like we’re ‘going against the grain’. This is the case even in everyday social situations, let alone exceptional circumstances when your life is under threat. Perhaps we therefore need to place the idea of ‘speaking out and standing up for your values’ on more of a pedestal culturally - something that actually trumps social acceptance as a desirable and heroic act.

7. It takes effort to be civilised as an individual

Before we explore this lesson, let us firstly define what we mean by ‘civilised’. In this booklet, when we talk about being ‘civilised’ we certainly don’t mean it in an old-fashioned, prudish, British Empire ‘taming the natives’ way, but in the way historian Timothy Garton Ash describes the word ‘civilisation’ in one of its earliest senses, as meaning: “the process of human animals being civilised - by which we mean...achieving a mutual recognition of human dignity, or at least accepting in principle the desirability of such a recognition.” 10

We noted in the first lesson that civilisation is fragile and we should not take it for granted, but instead cherish it and work to protect it. With all of the lessons listed above that have followed it, we can draw a broader conclusion - that civilisation requires effort. It takes effort not to be prejudiced, violent or cruel. Kindness, compassion and holding oneself back from judgement or lashing out - these

things take effort.

As we can see from some of the earlier lessons, decivilisation (and many of its symptoms such as cruelty and ‘turning a blind eye’) can be associated with a lack of effort or courage; passivity, a failure to pay attention. A wide range of the qualities needed for civilised behaviour require effort, including:

- Self awareness - being aware of our own individual tendencies towards particular noncivilised thoughts and behaviour (such as having a ‘short fuse’, being annoyed at your ego being dented, insecurity, being scared to disobey orders etc.), and being aware of them as they arise in us.

- Self restraint - once we’ve identified the traits above, being able to avoid them before (and when) they arise, so that they rise to the surface less frequently. This might involve having ‘coping strategies’ to deal with them or simply trying harder to be self disciplined. And yes, this can be hard to do but as this section states, these things take effort - effort that we should feel obliged to put in if we want to develop a more civilised and peaceful society.

- Pro-civilised behaviour - sharing, helping, reaching out - all of these behaviours can take effort, especially when we’re not in the mood for doing them (see ‘self awareness’ above). But again, some of the most important times to exercise these pro-civilised behaviours are when ‘the going gets tough’ and we are under pressure. For example it’s easy to be nice to someone when they’re being nice to you - but when they’re not, it takes effort.

- Vigilance - being aware of what’s happening and what’s being said around us - having a nuanced and well-informed sense of the ‘atmosphere’ that our lives are being lived in at a given moment. We need to be vigilant as changes for the worse in language, policy and behaviour can happen continually around us if we are not well informed (for example about politics) or accustomed to being ‘tuned in’ to them. This is the case in our immediate family and social groups, as well as the broader media and world at large. The mundanity of cruelty and violence makes it easy to ratchet up aggressive language, violence and other decivilised behaviour without people really noticing, so we need to be alert to this all the time, both around us and from every section of wider society.

- Speaking up (or ‘resisting’) - when we see or hear things happening that are against our moral instincts we need to make the effort (and have the courage) to speak out and take action against them.

We should each consider whether we need to apply these principles to our own lives. But this is about way more than just speaking up or following your values. Civilisation seems to require each of us to see ourselves as more than just an individual looking after our own interests. You can try to isolate yourself, look after your own interests and step out of involvement with the rest of the world, but we live on a planet with a large number of other people on it, so most of us can’t completely isolate ourselves and are bound to come across other people sooner rather than later. Contact with these people brings the need for some form of effort - at the very least in communicating with them and dealing with the competition for resources, food, water, shelter and other things that they represent.

So, it takes a certain level of effort to deal with the existence of other people, regardless of whether or not you treat these other people in a civilised fashion. But, it takes even more effort to coexist with people in a harmonious, civilised way - for example, to think about the effect of our actions on others, to empathise, to share and to protect other people and put their interests above our own occasionally.

We need to get across to people (and society at large) that this additional effort is worthwhile - in fact, as we have seen in this booklet, it could be argued that our peaceful coexistence depends on it.

Ultimately then, the Holocaust not only shows us that we are intrinsically linked to each other’s wellbeing, but that a good, civilised society needs to have (and continually foster) a sense of collectivism - a sense that we are ‘in it together’, and are each part of a bigger whole rather than as isolated individuals pursuing our own desires, as the Holocaust and many other examples show that the former is the route to a more peaceful and civilised society. For example, speaking up could result in a bad situation for you but it could save many other people – and maybe we need to have this sense of being more linked together in order to appreciate this properly.

8. It takes effort to have civilisation - as a society

The need to expend effort in order to achieve a truly civilised society applies not just to us as individuals, but to our society as well, and the institutions, customs and values that support it.

A civilised society doesn’t come for free, so we all have to collectively invest time, effort and money in it. This includes investment in the following areas of society:

- Education - we need to educate both children and adults about ‘civilisation’ as an active, participatory idea, in order to strengthen our foundations both as individuals and as a broader society as much as possible against the development of horrors like the Holocaust in future. Below are some areas in which we think people should be educated that are important to promoting pro-civilised thinking and behaviour:

- What civilisation is and why it matters - when there has been relative stability in society for a long period, people need to be informed and then regularly reminded of how fragile civilisation is, as well as what a society lacking in civilisation is like, so that we learn to appreciate how important it is and not take it for granted. We also need to show people that civilisation requires effort, but that this additional effort is worthwhile - as our peaceful coexistence depends on it.

- A realistic view of human beings - we need to teach both children and adults the latest thinking about what human beings are actually like - in other words, how we actually think and behave. This may require us to draw out some broad, rough characterisations of the human being, but these will undoubtedly be more accurate than the dated, ‘morally tinted’ lens that most people currently view human beings through. We could draw upon a range of disciplines to build this ‘modern view’ of the human being - including biology, neurology, psychology and sociology. This picture could be used not just to provide the general public with a more accurate view of human beings (although this is useful in itself), but could also be put to countless important practical uses. For example, to set realistic expectations about human behaviour, teach people what our vulnerabilities are to destructive or aggressive thinking and behavior, and how we can protect ourselves against these vulnerabilities – both in ourselves and others.

- The art of being civilised - we need to spell out what ‘pro-civilised’ thinking and behaviour looks like, and what principles, habits and skills it consists of - so that we can teach it to people and embed it in our values, customs and institutions. We then need to educate people in the life skills, habits and behaviours that promote civility. When teaching these principles, we also need to show why each aspect of pro-civilised thinking and behaviour is so important - and thus transforming principles like ‘empathy’ from being soft and frilly ‘nice to haves’ into concrete, essential tools for a civilised society. Here are a selection of possible habits, skills and behaviours for a ‘civility’ toolkit:

-

Kindness - simply the principle of living your life with the aim of making other people’s lives better when you can, and making the effort to be pleasant to them.

-

Compassion - making the effort to stay aware of other people’s welfare and helping them when you can.

-

Empathy - enhancing people’s ability to put themselves in the shoes of others - including trying to understand what it’s like to experience certain emotions, thoughts, sensations and situations that they may not have experienced before, but that other people have. For example, trying to understand what it’s like to feel lonely.

-

Our effects on others - as part of the above point, we should also teach people to use empathy in positive ways - for example, thinking before they act about the effects that their actions or words might have on others. Let us make people sensitive to their impact on others - and not just the big, obvious effects (such as the effect of hitting someone), but to also be sensitive to the smaller, nuanced effects that the little things they say or do can have, and be aware of how these can not just affect others but can also become part of a bigger cumulative movement. For example, even a seemingly minor one-off act such as using a lazy racial stereotype means you’re contributing to making it seem acceptable to dismiss another race of people.

-

Self awareness - developing an awareness of our own individual internal mechanisms, habits, thought processes and triggers - and developing coping mechanisms to deal with those that could lead to de-civlilised behaviour. People sometimes fail to see which of their thoughts or actions could sow the seed for violence or terror, or recognise when when their thoughts or actions have crossed the line into this state of affairs (e.g. into coercive behaviour) - and perhaps we need to make people more aware of this. Learning of this type might include understanding what uncivilised behaviour can consist of - for example the fact that abuse doesn’t have to just consist of physical violence. There are obvious everyday benefits that this type of education could have for people in areas such as personal relationships, even without considering their longer-term benefits for civilised society.

-

Self control - as they develop the various forms of self awareness noted above, people must also learn how to anticipate andmodify their behaviour in the light of this awareness - in other words, develop (and continually practice) the skills and habits of self control.

-

A strong moral compass - we need to teach people to understand morality better - both as a concept in itself and how to apply it intelligently to their daily lives. Alongside this, we need to encourage people to develop both a stronger sense of their ‘moral compass’ - what they feel to be right and wrong - and the bravery and consistency to stand by their moral standards. This is linked with helping people to develop a clearer sense of, and pride in, their own identity, even if it differs from others. We’re all inclined to follow the herd to some extent and do what we can to be socially accepted, and this can make it difficult to speak out when it goes against the social grain. But we should teach people that standing up for values is more important than social acceptability - indeed, we need a cultural shift to portray it as heroic.

-

Speaking up and taking action - strongly connected with the previous point, we need to teach people to speak up and protest when they disagree with something, rather than just letting it happen or ignoring it – from lower level occurrences such as seeing someone drop litter, through to standing up to bullies, and even to the scale of protesting against government policies, as ultimately this can provide traction to prevent evil things happening, and at the very least lays the foundations for an active, participative democracy.

-

Collectivism - there may sometimes be a price to pay for speaking up and taking action. This price may be relatively minor (such as temporary social isolation for voicing an unpopular view) but, at the sharp end of crisis (in situations like the Holocaust) it may be risking one’s own life. This may be a more controversial suggestion, but perhaps teaching should ask people to consider what price they’d be prepared to pay for the sake of others – and their civilisation. This is is not to suggest that we should be teaching people that their own life is not worth more than other people’s, but instead to open up the idea of collectivism - to see ourselves as intrinsically linked to each other’s well-being and able to affect it for the better or worse. And to ask whether there are situations in which we’d each be prepared to take a bigger risk in speaking up and taking action in order to protect the welfare of that bigger whole of which we are each part.

-

- Culture - as a society, we should promote ideas and cultural orthodoxies that encourage empathy, honesty, understanding, compassion and courage - and reconsider those that promote the opposite. Even at a brief glance, we can identify a number of aspects of modern society that militate against pro-civilised values, thinking and behaviour. For example, we noted earlier (in lesson 7) that civilisation requires us to see ourselves as part of a bigger whole rather than isolated individuals. Sadly, in recent decades, the dominant economic philosophy, which has subsequently become a social and cultural trend, has been one of individualism rather than collectivism. It can be argued that this form of neoliberal capitalism is focussed on economic growth rather than human flourishing, and as a result leads to thinking and behaviour that encourages de-civilised rather than pro-civilised behaviour - including competition, greed, envy and self-interest, as opposed to collaboration, equality and compassion. Margaret Thatcher noted in 1987 that ‘There is no such thing as society’11 and this point appears to have become the reality as a result of her and others’ policies.We are also living at a time with many human geopolitical challenges – from the plight of refugees to the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) – and we should take care to address them in a way that puts humanity and ‘pro-civilised’ values first. We should be wary of any doctrines, views or ideas – whether political or religious – that separate people from each other or allocate different levels of humanity to different groups of people.

- Institutions – we should strengthen and set up institutions that support these pro-civilised ideas, including (but ranging vastly beyond) organisations to promote learning about the Holocaust (such as the Holocaust Education Trust). Ultimately, we should promote organisations and institutions helping people to learn about the world, other people and live with in a positive way - from local libraries to not-for-profit organisations like Life Squared, through to international bodies such as the United Nations.

Final thoughts

This has perhaps been a challenging booklet to read at times, as it has touched on some of the darkest episodes in human history, yet we hope it has also shown some important reasons for optimism for the future.

We should never think that events like the Holocaust can’t happen again. Indeed, the fact that genocide has happened around the world since proves that they can. These tragedies however bring us lessons about human beings and human society that we can – and must – learn from, so that we can not only help to reduce the probability (or regularity) of such events, but at the very least can make a collective effort to improve the way we treat each other and live together on our planet.

And in this way, we can salvage some hope from the most hopeless places.

References

1 It always lies below, Timothy Garton Ash, The Guardian, 8th September 2005, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/sep/08/hurricanekatrina.usa6

2 Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt, introduction by Amos Elon, Penguin, London 2006, p.287

3 Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt, introduction by Amos Elon,Penguin, London 2006, p.xiii

4 Thinking, Fast And Slow, Daniel Kahneman, Penguin, London 2012

5 Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt, introduction by Amos Elon, Penguin, London 2006, p.287

6 Man’s search for meaning, Viktor Frankl, Rider 2004, p.23

7 The destruction of the European Jews, Raul Hilberg, Holmes & Meier 1985, P.213

8 The destruction of the European Jews, Raul Hilberg, Holmes & Meier 1985, P.246

9 The destruction of the European Jews, Raul Hilberg, Holmes & Meier 1985, P.294

10 It always lies below, Timothy Garton Ash, The Guardian, 8th September 2005, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/sep/08/hurricanekatrina.usa6

11 Margaret Thatcher interview for Woman’s Own, 23rd September 1987 http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689

Further resources

To hear more stories and find out more about the Holocaust, check out these resources:

Organisations

Holocaust Educational Trust www.het.org.uk

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum www.ushmm.org

Films

Shoah, Dir Claude Lanzmann, 1985

Night will fall, Dir Andre Singer, 2014

Books

Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt, introduction by Amos Elon, Penguin, London 2006

The destruction of the European Jews, Raul Hilberg, Holmes & Meier 1985

I shall bear witness: - the diaries of Victor Klemperer 1933-41, translated by Martin Chalmers, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1998

To the bitter end - the diaries of Victor Klemperer 1942-45, translated by Martin Chalmers, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1999

Man’s search for meaning, Viktor Frankl, Rider 2004

Articles

Article http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/10/the-day-israel-saw-shoah

© 2016 Richard Docwra

Published by Life Squared. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the publisher’s permission. Please contact Life Squared if you wish to syndicate this information.

You May Also Like

Ecological intelligence

Daniel Goleman discusses the important virtue of Ecological Intelligence.

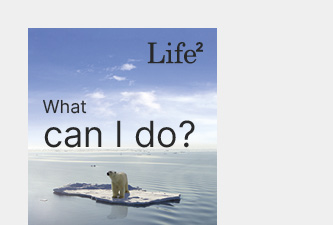

What can I do?

The most important steps you can take to properly reduce your carbon footprint.